|

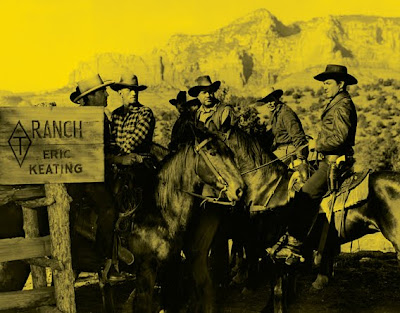

George “Gabby” Hayes with Karolyn Grimes (hopefully not too soon after his buttermilk and cornbread lunch) |

SM: As a child actor, were there different directors who would take the time to work with you a lot?

KAROLYN GRIMES: Oh yeah, uh-huh. But some of them were scary. I mean John Ford (Rio Grande, 1950) was. [Laughing]

He was intimidating?

Oh, yeah! Yeah, yeah, yeah!

He didn’t have a lot of time for child actors?

No, no, no, no. And he had a big temper. He didn’t care who was there, whether there was a kid there or not; the words flew. But Leslie Fenton (Pardon My Past, 1945) was a very nice director, I remember him. Henry Koster on The Bishop’s Wife (1947) was super. He’d get on the floor and tell me what to do. Of course, Frank Capra (It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946) was just delightful.

What are your memories of “Gabby” Hayes?

He was fun to be around. When he was off camera he acted totally different [than his screen persona]. He was a very capable man, very smart. One thing I will never, ever forget is his lunch. They had all the food catered, tables and tables of all this delicious food. But every single day, he ate the same thing: buttermilk with cornbread in a glass, and I thought it was the sickest stuff I’d ever seen! It stunk, it was awful, it would get in his beard. [Laughs] And I remember he did not want to ride in that stagecoach. He did not ride in that stagecoach. He had a stunt double, he didn’t get up there. And he thought it was dangerous for me and Catherine Craig to do it. But he didn’t win; we did it.

And you had fun doing it!

I had a blast, I didn’t think of it as dangerous at all. I thought it was great. But anything could have happened. Horses stumble, fall. It wouldn’t have passed today. They had a [prop] stagecoach, with a thing that the men pushed and pulled on either side to make it jump around. They told me the horses were running away with me and I was supposed to hang out the window. They tell you everything you’re supposed to do. So it was fun; I mean, everything I did on that whole set was fun. I loved the western town and all the horses. And to ride on a stagecoach with all those horses? Wow, for goodness sakes! And what’s really funny is there’s [supposed to be] a dead man in the back of that stagecoach. [Laughing] When you think about the whole thing, [Myrtle is] sitting in this stagecoach, just saw this man shot dead – and it didn’t bother me one bit! ––Originally published in the October 2006 issue of Sedona Monthly