Showing posts with label Howard Hughes. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Howard Hughes. Show all posts

Monday, August 22, 2011

Monumental Pictures, Part 2

Even though Monument Valley has less than four minutes of screen time in Stagecoach, it made an indelible impression on Moviegoers in 1939. But it wasn’t the first time they’d seen it in a film. In late August 1938, six weeks before he brought John Ford to Monument Valley to scout locations for Stagecoach, Flagstaff rancher/movie coordinator Lee Doyle arranged for an MGM crew to film exteriors there (and in Sedona) for George B. Seitz’s Out West With the Hardys; inexplicably, the Mickey Rooney-starring sitcom would pull into theaters (more than three months before Stagecoach) with no easy-to-ID Monument Valley real estate in sight. In 1940, Seitz returned to Monument Valley for the third time to direct indie producer Edward Small’s Kit Carson with Jon Hall.

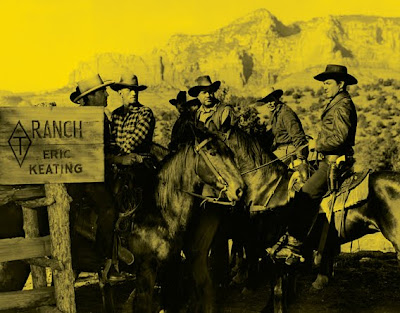

After Stagecoach delivered boffo box office, moviemakers rolled into Monument Valley. Before he was replaced by producer Howard Hughes, Howard Hawks planned to direct a scene or two there for Jane Russell’s controversial “sex Western” The Outlaw at the exact same time in 1940 that MGM had a unit among the buttes shooting action sequences for its competing Billy the Kid. MGM would send a cameraman back in 1945 to film rock eye-candy backdrops for George Sidney’s Judy Garland songfest, The Harvey Girls.

Following the lifting of World War II travel restrictions, a Republic Pictures second unit shot a chase sequence in Monument Valley for its 1946 William Elliott Western, Plainsman and the Lady (aka Drumbeats Over Wyoming). Oh, by the way, Wild Bill’s people beat John Ford to the valley by a few days when he went back (his first visit since Stagecoach) to make My Darling Clementine for Twentieth Century-Fox. Concurrently, Yakima Canutt, Stagecoach’s stunt coordinator, was there too, directing the main title action of John Wayne’s Sedona-based Angel and the Badman for Republic.

Curiously, not every Monument Valley movie was actually filmed in Monument Valley. Then as now, Hollywood producers were quick to pounce on trends, so to cash in on the valley’s post-Stagecoach mythic status, Poverty Row studio Monogram Pictures released King of the Stallions (aka Code of the Red Man) a 1942 obscurity that on-screen credits ballyhooed as being “filmed in Monument Valley, Arizona.” In fact, the “Monument Valley” turf seen in the flick is mostly Sedona’s Red Rock Country, courtesy of extensive footage lifted from Grand National Films’ 1938 King of the Sierras, a slapdash B picture that quickly put fading Rex the Wonder Horse out to permanent show-biz pasture.–– Joe McNeill. Originally published in the July/August 2011 issue of Sedona Monthly

Monday, July 25, 2011

Burl Trouble

In 1948, popular folksinger Burl Ives was one of the main selling points for RKO Radio Pictures when it was promoting Station West, the partly filmed-in-Sedona cowboy film noir; he was fourth-billed in the credits and featured in all promotional materials. But when the film was re-released in 1954, Ives’ name mysteriously vanished, and his screen time greatly reduced. Bizarrely, Ives’ role in Station West seems to have been a little-noticed casualty of Cold War paranoia.

In May 1948, Obsessive-Compulsive millionaire Howard Hughes took control of financially struggling RKO. A virulent anti-Communist, Hughes fired approximately 1,900 of RKO’s 2,500 employees, virtually shutting down production for six months while his investigators dug into remaining workers’ pasts. “It is my determination to make RKO one studio where the work of Communist sympathizers will not be used,” Hughes told the Hollywood Reporter in April 1952. To that end, Hughes set up a “security office” at RKO; one of its tasks was to purge suspected Communists from the credits of older RKO films being re-released to theaters.

Here’s where Ives appears to have run into a problem. In 1950, Counterattack: The Newsletter of Facts To Combat Communism, published a book called Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, which listed 151 people in entertainment and broadcast journalism linked to “subversive” organizations, either at the time or in the past. Red Channels claimed Ives had had past association with three obscure leftist organizations in the early 1940s.

But on Sept. 25, 1952, under the headline “Reds Dupe Artists, Senate Group Says,” The New York Times reported that the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee cited Ives and three other show business personalities as examples of how Communists were using the respected American entertainers to unwittingly strengthen subversive aims. Ives was not accused of being either a Communist or a deliberate “fronter.” In a statement included in the Times story, Ives wanted it on the record that he’d voluntarily gone before the Senate to show he “never knowingly approved anything Un-American.” He closed the statement by saying: “I am not and never have been a Communist.”

But on Sept. 25, 1952, under the headline “Reds Dupe Artists, Senate Group Says,” The New York Times reported that the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee cited Ives and three other show business personalities as examples of how Communists were using the respected American entertainers to unwittingly strengthen subversive aims. Ives was not accused of being either a Communist or a deliberate “fronter.” In a statement included in the Times story, Ives wanted it on the record that he’d voluntarily gone before the Senate to show he “never knowingly approved anything Un-American.” He closed the statement by saying: “I am not and never have been a Communist.”

By the looks of it, Hughes was not impressed. With no fanfare Ives’ name was erased from posters, ads, and the film’s credits when Station West was re-released to theaters in 1954. Look at the poster from 1948 (at top), which displays Ives’ name and image. This was typical of the film’s entire publicity campaign, which clearly aimed to leverage the folksinger/radio personality’s popularity. In ‘54, however, Ives is conspicuously missing from all promotional materials, such as the poster above– funny that the campaign now sported a “red” color scheme.––Joe McNeill

In May 1948, Obsessive-Compulsive millionaire Howard Hughes took control of financially struggling RKO. A virulent anti-Communist, Hughes fired approximately 1,900 of RKO’s 2,500 employees, virtually shutting down production for six months while his investigators dug into remaining workers’ pasts. “It is my determination to make RKO one studio where the work of Communist sympathizers will not be used,” Hughes told the Hollywood Reporter in April 1952. To that end, Hughes set up a “security office” at RKO; one of its tasks was to purge suspected Communists from the credits of older RKO films being re-released to theaters.

Here’s where Ives appears to have run into a problem. In 1950, Counterattack: The Newsletter of Facts To Combat Communism, published a book called Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, which listed 151 people in entertainment and broadcast journalism linked to “subversive” organizations, either at the time or in the past. Red Channels claimed Ives had had past association with three obscure leftist organizations in the early 1940s.

But on Sept. 25, 1952, under the headline “Reds Dupe Artists, Senate Group Says,” The New York Times reported that the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee cited Ives and three other show business personalities as examples of how Communists were using the respected American entertainers to unwittingly strengthen subversive aims. Ives was not accused of being either a Communist or a deliberate “fronter.” In a statement included in the Times story, Ives wanted it on the record that he’d voluntarily gone before the Senate to show he “never knowingly approved anything Un-American.” He closed the statement by saying: “I am not and never have been a Communist.”

But on Sept. 25, 1952, under the headline “Reds Dupe Artists, Senate Group Says,” The New York Times reported that the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee cited Ives and three other show business personalities as examples of how Communists were using the respected American entertainers to unwittingly strengthen subversive aims. Ives was not accused of being either a Communist or a deliberate “fronter.” In a statement included in the Times story, Ives wanted it on the record that he’d voluntarily gone before the Senate to show he “never knowingly approved anything Un-American.” He closed the statement by saying: “I am not and never have been a Communist.”By the looks of it, Hughes was not impressed. With no fanfare Ives’ name was erased from posters, ads, and the film’s credits when Station West was re-released to theaters in 1954. Look at the poster from 1948 (at top), which displays Ives’ name and image. This was typical of the film’s entire publicity campaign, which clearly aimed to leverage the folksinger/radio personality’s popularity. In ‘54, however, Ives is conspicuously missing from all promotional materials, such as the poster above– funny that the campaign now sported a “red” color scheme.––Joe McNeill

Saturday, May 22, 2010

The Kid Stays in the Picture

Billy The Kid was a wanted man in 1930s-’40s Hollywood. After the release of MGM’s big budget Billy the Kid in 1930 (directed by King Vidor and starring Johnny Mack Brown), the character made a brief reappearance (played by uncredited Lynton Brent) in Tom Mix’s The Texas Bad Man, released by Universal Pictures in 1932. The desperado laid low before resurfacing in Republic’s Billy the Kid Returns (1938), this time as half of a dual role played by “king of the cowboys” Roy Rogers in his second starring film.

Two years later, ultralow-budget Producers Releasing Corp. (PRC) initiated a Saturday matinee series with Billy the Kid Outlawed (1940), which rewrote history by changing The Kid from horse-thieving gunman to benevolent Stetsoned Robin Hood. “B’’-movie cowboy Bob Steele played him in the first six films, released during the 1940-’41 season. Steele was replaced by former Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers/Tarzan star Buster Crabbe, who headlined thirteen more PRC Billy the Kid cheapies between 1941 and 1943. In these, the real-life character’s name (or alias) Billy Bonney was changed to Billy Carson, reportedly because of complaints that the films glorified a notorious criminal. Crabbe continued with the series for twenty-three more films into 1946.

Two years later, ultralow-budget Producers Releasing Corp. (PRC) initiated a Saturday matinee series with Billy the Kid Outlawed (1940), which rewrote history by changing The Kid from horse-thieving gunman to benevolent Stetsoned Robin Hood. “B’’-movie cowboy Bob Steele played him in the first six films, released during the 1940-’41 season. Steele was replaced by former Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers/Tarzan star Buster Crabbe, who headlined thirteen more PRC Billy the Kid cheapies between 1941 and 1943. In these, the real-life character’s name (or alias) Billy Bonney was changed to Billy Carson, reportedly because of complaints that the films glorified a notorious criminal. Crabbe continued with the series for twenty-three more films into 1946. MGM’s 1941 Billy the Kid remake with Robert Taylor was the first Technicolor movie shot in Sedona, but the studio with “more stars than there are in heaven” fretted over competition with millionaire Howard Hughes’ The Outlaw, finished early that same year, but not released for another 18 months, largely over censors’ objections to perceived erotic content and the camera’s leering fixation on Jane Russell’s breasts. Arizona location filming began in Tuba City, with additional photography slated for Sedona, but after two weeks Hughes abruptly ordered the production back to Hollywood without explanation. The Outlaw finally opened in San Francisco on February 5, 1943, but seven weeks later, after having grossed the then-tidy sum of $158,000, the eccentric Hughes, for reasons he never explained, pulled the picture out of circulation.

MGM’s 1941 Billy the Kid remake with Robert Taylor was the first Technicolor movie shot in Sedona, but the studio with “more stars than there are in heaven” fretted over competition with millionaire Howard Hughes’ The Outlaw, finished early that same year, but not released for another 18 months, largely over censors’ objections to perceived erotic content and the camera’s leering fixation on Jane Russell’s breasts. Arizona location filming began in Tuba City, with additional photography slated for Sedona, but after two weeks Hughes abruptly ordered the production back to Hollywood without explanation. The Outlaw finally opened in San Francisco on February 5, 1943, but seven weeks later, after having grossed the then-tidy sum of $158,000, the eccentric Hughes, for reasons he never explained, pulled the picture out of circulation.When Hughes decided to reissue The Outlaw in 1946, Hollywood’s self-censoring Breen office saw red over its naughty publicity campaign (“What are the two great reasons for Jane Russell’s rise to stardom?” and “How would you like to tussle with Russell?”), which led it to withdraw its seal of approval. Crazy-like-a-fox Hughes went ahead and re-released the picture anyway, to widespread local bans and canceled theater bookings. But proving there’s no such thing as bad publicity (especially when the buzz concerns sex), The Outlaw became a sensation despite widespread bad reviews, and eventually took in more than $3 million in the United States alone.––Joe McNeill

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)