MGM sent a film film crew to Sedona—its last to make the trip to Red Rock Country for twenty years—in May 1943 to photograph scenes for Roaming Through Arizona, a one-reel “Traveltalks” short released in 1944 that included Technicolor views of Oak Creek Canyon. An entry in the long-running series produced by James A. FitzPatrick, Roaming Through Arizona is a simple travelogue that extolls the virtues of various state attractions, although the Grand Canyon, filmed during FitzPatrick’s visit to Arizona, isn’t included here; that footage was saved for use in a separate Traveltalk, Grand Canyon, Pride of Creation (1943).

The nine-minute Roaming Through Arizona, silent with a voice-over narration and music, does offer pleasing postcard views of the Mission of San Xavier, south of Tucson, as well as the statues of World War I aviator Frank Luke (on the grounds of the state capitol building in Phoenix) and Captain William “Bucky O’Neill” (organizer of the Arizona unit of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders) in Prescott, along with Prescott’s Granite Dells. It tells the histories of the cliffside mining town of Jerome, the Petrified Forest National Monument, and Wickenburg’s Hassayampa Well, Rodeo, and wedding chapels.

However, Sedona is the only location visited in Roaming Through Arizona that’s not identified by name, despite the beautiful views of Bell Rock, Capitol Butte, and Gibraltar Rock (near Lee Mountain). The intimidating switchbacks of Oak Creek Canyon are mentioned by name in passing, but FitzPatrick mistakenly gives credit to Mayhew’s Oak Creek Lodge as the place “where Zane Grey wrote his famous book The Call of the Canyon.” The film fades to black as the camera offers a sweeping panoramic shot of Sedona’s anonymous terrain while an offscreen chorus warbles “Home on the Range.”––Joe McNeill

Showing posts with label MGM. Show all posts

Showing posts with label MGM. Show all posts

Monday, December 26, 2011

Monday, June 20, 2011

Sue Ane Langdon Exposes ‘The Rounders’

|

| Henry Fonda and Glenn Ford tip their hats to Hope Holiday and Sue Ane Langdon. |

JM: First off, I want you to know that I get a big kick out of The Rounders...

SUE ANE LANGDON: Oh, thank you! I think it’s a loveable movie. It’s a great movie for horse lovers – although you could learn to hate them, too (laughing). But you can never hate [equine co-star] Ol’ Fooler! It’s a wonderful movie about people, a great study of those two guys.

It really holds up. It’s still funny.

It still plays. I went to a private showing for the Kiwanis Club, I think it was in Thousand Oaks, California. And Peter Ford, Glenn’s son was there and I didn’t realize that he and Peter Fonda (Henry’s son) were in the movie. They’re in the big barroom fight scene; they hit each other. So next time you see it, if you see a fella that looks like Glenn Ford, but younger, that’s his son. He looks just like him. And Peter Fonda you may know from his other movies.

What are your memories of Burt Kennedy, The Rounders’ director?

Oh, I loved Burt. Fortunately, I was able to spend a lot more time with him later. We would see each other throughout the years, at parties and things. We began to go every year to his birthday party. Burt did some very nice things for me and he was just a darling man. He was a dear man – almost the “king of the Westerns,” next to John Ford. He made so many Westerns. I miss him very much.

When you were in Sedona, did you get a chance to sightsee or was it just all work?

I think it was mostly just work, work, work – but where we worked was sightseeable. Where is there a place [in Sedona] that’s not sightseeable? As we drove in today, I remembered the scene where Hope Holiday and I are leaning over the car, the scene where Glenn and Henry first spot us and they skid to a halt. We’re leaning over, looking under the hood because the vehicle has stopped and I say something like “I think it’s the carburetor or the brakes,” whatever that infamous line was. But that’s no longer a two lane highway. That’s all it was when we shot there.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

Love, the Second and Third Time Around

|

| Chill Wills |

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Blake Edwards: That’s Life!

|

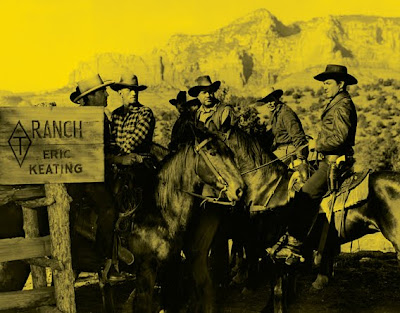

| Cattlemen Karl Malden, Charles Grey and William C. Bryant (rear) go gunning for sheepherders – and maybe a few MGM suits – in Wild Rovers. |

His feud with MGM began with the 1971 western Wild Rovers, which photographed scenes at Sedona, Flagstaff, Monument Valley and 46 other Arizona locations. Edwards maintained that he conceived the film as a “classic Greek tragedy,” but after the studio arbitrarily chopped 40 minutes from his cut, it left nothing, he lamented, but a prototypical cowboy movie.

“There was no discussion; an integral part was simply removed” Edwards griped to The New York Times in 1972. “If I take a chair and remove one leg, you still have a chair,” he said to rationalize his anger with the tampering, “but it won’t stand up, will it?”

|

| Blake Edwards |

But Edwards had the last laugh on MGM. Most of Wild Rovers’ deleted footage was restored for the film’s 1986 home video release, which resulted in a critical reevaluation of the film’s many merits. Unfortunately, Edwards’ cut of Wild Rovers, which can be seen occasionally on Turner Classic Movies, has yet to be released on DVD.––Joe McNeill

Monday, September 20, 2010

‘Stay Away’ WAS a Play

Elvis Presley made his comeback in Las Vegas but he had a comedown in Sedona, where most of Stay Away, Joe, arguably the bottom of the barrel of his film career, was shot in 1967. The most unfortunate side effect of decades of critical trash talk is that the movie hides one of the most beautiful Sedona moments ever filmed: The main title sequence features Elvis singing “Stay Away” while you see a breathtaking aerial sweep over the open spaces and jagged peaks of the red rock landscape play out on the screen.

Elvis Presley made his comeback in Las Vegas but he had a comedown in Sedona, where most of Stay Away, Joe, arguably the bottom of the barrel of his film career, was shot in 1967. The most unfortunate side effect of decades of critical trash talk is that the movie hides one of the most beautiful Sedona moments ever filmed: The main title sequence features Elvis singing “Stay Away” while you see a breathtaking aerial sweep over the open spaces and jagged peaks of the red rock landscape play out on the screen.

But Elvis’ flop Sedona film was a flop on the Great White Way first. When I reported that the novel Stay Away, Joe previously had been the basis of a Broadway bomb entitled Whoop-Up, some people accused me of putting them on. As this theatrical footnote has rarely ever been acknowledged in accounts of the movie, I was challenged to provide proof; after much coast-to-coast rummaging, behold the Whoop-Up smoking gun: a Playbill from Jan. 12, 1959.

Somewhat familiar names involved in the musical comedy included Ralph Young as Joe (the role later played by Elvis), who would go on to co-star in sexploitation auteur Doris Wishman’s Blaze Starr Goes Nudist in 1960 before gaining renown in Vegas and supper clubs as half of the duo Sandler and Young; and Norman Gimbel, who would later compose the themes for TV’s Happy Days and Laverne and Shirley.

Alas, despite the bounding enthusiasm of the “Native American” chorus boys you see on the Playbill cover, the show closed after only 56 performances. If I hear about any 52nd anniversary celebrations in January 2011, I’ll let you know. In the meantime, there’s a full account of this long-forgotten Broadway dud in the Stay Away, Joe chapter of Arizona’s Little Hollywood.––Joe McNeill

Monday, May 31, 2010

Untrue West

The Criterion Collection’s Blu-ray release of John Ford’s Stagecoach is a keeper––the film looks better than it has in decades and the disc comes fully loaded with a strongbox full of terrific special features. Unfortunately, the old hash about John Ford’s “discovery” of what would become his favorite filming location is reheated once again in the ironically titled video supplement True West: Harry Goulding and Monument Valley.

You know the story: Indian trader Goulding, worried by the plight of his starving Navajo friends, drives 650 miles to Los Angeles in a rickety old pickup truck––much of the trip on bumpy, unpaved dirt roads, mind you––armed with snapshots of the completely unknown Monument Valley to insist that Ford shoot his new Western there. Ford immediately snaps at the bait, flying pronto to Arizona with a crew of dozens of people–– in one version of the tale he even beat Goulding back to Monument Valley––to heroically save the Navajo and create an iconic American movie location.

At least that's the way it happened inside the brain of an ingenious studio flack. After spending more than seven years delving into the movies made in northern Arizona I haven’t uncovered a shred of proof that Harry Goulding had anything more to do with Stagecoach than renting the basement of his trading post as dorm room for a handful of crew laborers. Ford and the movie’s other top dogs didn’t even bunk in Monument Valley during filming, they stayed at the actual base of operations, the Wetherill and Colville Trading Post and Lodge in Kayenta, twenty-five miles away. So if Harry Goulding brought together John Ford and Monument Valley, why wasn’t his trading post leased as company headquarters? That seems to be the least Ford could have done to reward Goulding for the trouble he had allegedly taken to broker the deal. What’s more, if Goulding had played such a vital role in bringing Ford to Monument Valley, why was his Navajo rescue mission––surely a press agent's dream story––not mentioned in print until 1953, fourteen years after Stagecoach rolled into theaters and, conveniently, both Wetherill and Colville were dead?

Stagecoach is one of the great Hollywood films, written about and analyzed since the day it hit theaters in 1939, so it boggles the mind that no historian has taken the time to sniff around Flagstaff to dig up the truth about how it was created. The Coconino Sun, the town’s only newspaper in those days, covered Stagecoach‘s production from the moment Ford first came to northern Arizona to scout locations right up to its world premiere engagement––in Flagstaff, by the way, and not Los Angeles (that’s another reality long ignored by historians, but a story to save for another time).

So here are a few documentable, but less than legendary facts: In late September 1938, Flagstaff rancher Lee Doyle, who’d worked as Hollywood’s northern Arizona contact man since 1923, received a telegram from Stagecoach’s production manager asking him to help “look for locations in the Painted Desert and in Monument Valley.”

A week later The Coconino Sun reported that Ford and his associates met Doyle in Flagstaff to begin selecting locations and to make arrangements for bringing in a company of actors and technicians. Ford, Doyle and the rest of the Hollywood group checked into Wetherill and Colville’s in Kayenta; their signatures in the Lodge’s guest register, which survives in the Wetherill family archive, prove the scouting party stayed there for the remainder of their three day visit and not at Goulding’s in Monument Valley. Ford returned to Wetherill and Colville’s when filming began and he shacked there for the entire time he was on location. It's interesting to note that even though some spillover crew members were housed at his trading post, Harry Goulding wasn’t once mentioned by name during the three weeks The Coconino Sun covered Arizona filming.

There are a few other pesky details about the making of Stagecoach that have been ignored by the Ford/Goulding/Monument Valley mythologizers, including MGM records that confirm the studio had a film crew shooting second unit exteriors in Monument Valley for its Mickey Rooney sitcom Out West with the Hardys five weeks before Ford ever laid eyes on the place. What’s more, according to multiple Coconino Sun reports, Sedona was included as one of Stagecoach’s Arizona filming locations, chosen after Ford and his party made “motor trips over the Indian reservation and through Oak Creek Canyon, selecting sites for the different phases of the contemplated picture.” Sorry, movie fans, this buzz isn’t just spin–– it’s fact.––Joe McNeill

You know the story: Indian trader Goulding, worried by the plight of his starving Navajo friends, drives 650 miles to Los Angeles in a rickety old pickup truck––much of the trip on bumpy, unpaved dirt roads, mind you––armed with snapshots of the completely unknown Monument Valley to insist that Ford shoot his new Western there. Ford immediately snaps at the bait, flying pronto to Arizona with a crew of dozens of people–– in one version of the tale he even beat Goulding back to Monument Valley––to heroically save the Navajo and create an iconic American movie location.

At least that's the way it happened inside the brain of an ingenious studio flack. After spending more than seven years delving into the movies made in northern Arizona I haven’t uncovered a shred of proof that Harry Goulding had anything more to do with Stagecoach than renting the basement of his trading post as dorm room for a handful of crew laborers. Ford and the movie’s other top dogs didn’t even bunk in Monument Valley during filming, they stayed at the actual base of operations, the Wetherill and Colville Trading Post and Lodge in Kayenta, twenty-five miles away. So if Harry Goulding brought together John Ford and Monument Valley, why wasn’t his trading post leased as company headquarters? That seems to be the least Ford could have done to reward Goulding for the trouble he had allegedly taken to broker the deal. What’s more, if Goulding had played such a vital role in bringing Ford to Monument Valley, why was his Navajo rescue mission––surely a press agent's dream story––not mentioned in print until 1953, fourteen years after Stagecoach rolled into theaters and, conveniently, both Wetherill and Colville were dead?

Stagecoach is one of the great Hollywood films, written about and analyzed since the day it hit theaters in 1939, so it boggles the mind that no historian has taken the time to sniff around Flagstaff to dig up the truth about how it was created. The Coconino Sun, the town’s only newspaper in those days, covered Stagecoach‘s production from the moment Ford first came to northern Arizona to scout locations right up to its world premiere engagement––in Flagstaff, by the way, and not Los Angeles (that’s another reality long ignored by historians, but a story to save for another time).

So here are a few documentable, but less than legendary facts: In late September 1938, Flagstaff rancher Lee Doyle, who’d worked as Hollywood’s northern Arizona contact man since 1923, received a telegram from Stagecoach’s production manager asking him to help “look for locations in the Painted Desert and in Monument Valley.”

A week later The Coconino Sun reported that Ford and his associates met Doyle in Flagstaff to begin selecting locations and to make arrangements for bringing in a company of actors and technicians. Ford, Doyle and the rest of the Hollywood group checked into Wetherill and Colville’s in Kayenta; their signatures in the Lodge’s guest register, which survives in the Wetherill family archive, prove the scouting party stayed there for the remainder of their three day visit and not at Goulding’s in Monument Valley. Ford returned to Wetherill and Colville’s when filming began and he shacked there for the entire time he was on location. It's interesting to note that even though some spillover crew members were housed at his trading post, Harry Goulding wasn’t once mentioned by name during the three weeks The Coconino Sun covered Arizona filming.

There are a few other pesky details about the making of Stagecoach that have been ignored by the Ford/Goulding/Monument Valley mythologizers, including MGM records that confirm the studio had a film crew shooting second unit exteriors in Monument Valley for its Mickey Rooney sitcom Out West with the Hardys five weeks before Ford ever laid eyes on the place. What’s more, according to multiple Coconino Sun reports, Sedona was included as one of Stagecoach’s Arizona filming locations, chosen after Ford and his party made “motor trips over the Indian reservation and through Oak Creek Canyon, selecting sites for the different phases of the contemplated picture.” Sorry, movie fans, this buzz isn’t just spin–– it’s fact.––Joe McNeill

Saturday, May 22, 2010

The Kid Stays in the Picture

Billy The Kid was a wanted man in 1930s-’40s Hollywood. After the release of MGM’s big budget Billy the Kid in 1930 (directed by King Vidor and starring Johnny Mack Brown), the character made a brief reappearance (played by uncredited Lynton Brent) in Tom Mix’s The Texas Bad Man, released by Universal Pictures in 1932. The desperado laid low before resurfacing in Republic’s Billy the Kid Returns (1938), this time as half of a dual role played by “king of the cowboys” Roy Rogers in his second starring film.

Two years later, ultralow-budget Producers Releasing Corp. (PRC) initiated a Saturday matinee series with Billy the Kid Outlawed (1940), which rewrote history by changing The Kid from horse-thieving gunman to benevolent Stetsoned Robin Hood. “B’’-movie cowboy Bob Steele played him in the first six films, released during the 1940-’41 season. Steele was replaced by former Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers/Tarzan star Buster Crabbe, who headlined thirteen more PRC Billy the Kid cheapies between 1941 and 1943. In these, the real-life character’s name (or alias) Billy Bonney was changed to Billy Carson, reportedly because of complaints that the films glorified a notorious criminal. Crabbe continued with the series for twenty-three more films into 1946.

Two years later, ultralow-budget Producers Releasing Corp. (PRC) initiated a Saturday matinee series with Billy the Kid Outlawed (1940), which rewrote history by changing The Kid from horse-thieving gunman to benevolent Stetsoned Robin Hood. “B’’-movie cowboy Bob Steele played him in the first six films, released during the 1940-’41 season. Steele was replaced by former Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers/Tarzan star Buster Crabbe, who headlined thirteen more PRC Billy the Kid cheapies between 1941 and 1943. In these, the real-life character’s name (or alias) Billy Bonney was changed to Billy Carson, reportedly because of complaints that the films glorified a notorious criminal. Crabbe continued with the series for twenty-three more films into 1946. MGM’s 1941 Billy the Kid remake with Robert Taylor was the first Technicolor movie shot in Sedona, but the studio with “more stars than there are in heaven” fretted over competition with millionaire Howard Hughes’ The Outlaw, finished early that same year, but not released for another 18 months, largely over censors’ objections to perceived erotic content and the camera’s leering fixation on Jane Russell’s breasts. Arizona location filming began in Tuba City, with additional photography slated for Sedona, but after two weeks Hughes abruptly ordered the production back to Hollywood without explanation. The Outlaw finally opened in San Francisco on February 5, 1943, but seven weeks later, after having grossed the then-tidy sum of $158,000, the eccentric Hughes, for reasons he never explained, pulled the picture out of circulation.

MGM’s 1941 Billy the Kid remake with Robert Taylor was the first Technicolor movie shot in Sedona, but the studio with “more stars than there are in heaven” fretted over competition with millionaire Howard Hughes’ The Outlaw, finished early that same year, but not released for another 18 months, largely over censors’ objections to perceived erotic content and the camera’s leering fixation on Jane Russell’s breasts. Arizona location filming began in Tuba City, with additional photography slated for Sedona, but after two weeks Hughes abruptly ordered the production back to Hollywood without explanation. The Outlaw finally opened in San Francisco on February 5, 1943, but seven weeks later, after having grossed the then-tidy sum of $158,000, the eccentric Hughes, for reasons he never explained, pulled the picture out of circulation.When Hughes decided to reissue The Outlaw in 1946, Hollywood’s self-censoring Breen office saw red over its naughty publicity campaign (“What are the two great reasons for Jane Russell’s rise to stardom?” and “How would you like to tussle with Russell?”), which led it to withdraw its seal of approval. Crazy-like-a-fox Hughes went ahead and re-released the picture anyway, to widespread local bans and canceled theater bookings. But proving there’s no such thing as bad publicity (especially when the buzz concerns sex), The Outlaw became a sensation despite widespread bad reviews, and eventually took in more than $3 million in the United States alone.––Joe McNeill

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)