Showing posts with label The Outlaw. Show all posts

Showing posts with label The Outlaw. Show all posts

Monday, August 22, 2011

Monumental Pictures, Part 2

Even though Monument Valley has less than four minutes of screen time in Stagecoach, it made an indelible impression on Moviegoers in 1939. But it wasn’t the first time they’d seen it in a film. In late August 1938, six weeks before he brought John Ford to Monument Valley to scout locations for Stagecoach, Flagstaff rancher/movie coordinator Lee Doyle arranged for an MGM crew to film exteriors there (and in Sedona) for George B. Seitz’s Out West With the Hardys; inexplicably, the Mickey Rooney-starring sitcom would pull into theaters (more than three months before Stagecoach) with no easy-to-ID Monument Valley real estate in sight. In 1940, Seitz returned to Monument Valley for the third time to direct indie producer Edward Small’s Kit Carson with Jon Hall.

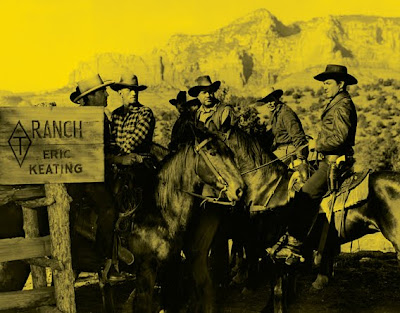

After Stagecoach delivered boffo box office, moviemakers rolled into Monument Valley. Before he was replaced by producer Howard Hughes, Howard Hawks planned to direct a scene or two there for Jane Russell’s controversial “sex Western” The Outlaw at the exact same time in 1940 that MGM had a unit among the buttes shooting action sequences for its competing Billy the Kid. MGM would send a cameraman back in 1945 to film rock eye-candy backdrops for George Sidney’s Judy Garland songfest, The Harvey Girls.

Following the lifting of World War II travel restrictions, a Republic Pictures second unit shot a chase sequence in Monument Valley for its 1946 William Elliott Western, Plainsman and the Lady (aka Drumbeats Over Wyoming). Oh, by the way, Wild Bill’s people beat John Ford to the valley by a few days when he went back (his first visit since Stagecoach) to make My Darling Clementine for Twentieth Century-Fox. Concurrently, Yakima Canutt, Stagecoach’s stunt coordinator, was there too, directing the main title action of John Wayne’s Sedona-based Angel and the Badman for Republic.

Curiously, not every Monument Valley movie was actually filmed in Monument Valley. Then as now, Hollywood producers were quick to pounce on trends, so to cash in on the valley’s post-Stagecoach mythic status, Poverty Row studio Monogram Pictures released King of the Stallions (aka Code of the Red Man) a 1942 obscurity that on-screen credits ballyhooed as being “filmed in Monument Valley, Arizona.” In fact, the “Monument Valley” turf seen in the flick is mostly Sedona’s Red Rock Country, courtesy of extensive footage lifted from Grand National Films’ 1938 King of the Sierras, a slapdash B picture that quickly put fading Rex the Wonder Horse out to permanent show-biz pasture.–– Joe McNeill. Originally published in the July/August 2011 issue of Sedona Monthly

Monday, May 9, 2011

Dick Jones Revisits ‘Virginia City’

|

| Dickie Jones (bandaged) with Errol Flynn in Virginia City. |

Dick Jones was one of Golden Age Hollywood’s busiest kid actors. At age four he began his career as the “World's Youngest Trick Rider and Trick Roper,” performing roping and riding tricks in “B” movie cowboy star Hoot Gibson’s rodeo. In the early ‘30’s he appeared in a few “Our Gang" shorts and by decade’s end had amassed dozens of credits in both "A" and "B" productions, such as John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln and Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (both 1939). In 1940 Jones gained movie immortality as the voice of Pinocchio in Walt Disney's animated classic; later that same year, he appeared in Virginia City, a western starring Errol Flynn and Humphrey Bogart that filmed scenes on location in Sedona. In a 2005 chat, Jones remembered Flynn’s pet tricks, Bogart’s quick exits, and Curtiz’s ‘goobers’––Joe McNeill

JM: Did you stay in Flagstaff while filming Virginia City?

DICK JONES: Oh yeah, I remember it real well. I just about ate myself to death with trout. I loved it. I actually came back to Flagstaff later that year to do The Outlaw.

What can you tell us about the personal appearance you made at Flagstaff’s Orpheum Theater while filming here?

I don’t remember it at all. I probably did a trick roping act, because that was the only thing I knew. (Laughing) I could strum a ukulele but that wouldn’t have been much!

Do you have memories of working with Errol Flynn in Virginia City?

The one thing I can remember was that he had this standard-sized schnauzer. He had that dog trained. [Flynn] had this swagger stick and he’d be slapping his boot with it, then he’d stop to talk to somebody and he’d slap them on their boot with that swagger stick. Then when he walked away the dog would come up and lift its leg up on them. I think [co-star] “Big Boy” Williams almost wanted to kill him!

I really enjoyed working with Errol Flynn. I worked with him again on Rocky Mountain (1950); that was my favorite of all the films I ever made. [Flynn] was one of the best journeyman actors. He knew his trade and worked his craft real well. What he did afterwards, that’s another story.

What do you remember of Humphrey Bogart?

I worked with him again after Virginia City, but he was very quiet and didn’t mess around with kids. It was always very much just work; you’d come in, the director would say ‘I want this, I want that,’ we’d rehearse our lines together one time, then boom – we’d do it and that’s it. I’d go back to school and he’d go back to his dressing room. So I didn’t spend much time with him. I’d have liked to.

What about Michael Curtiz, Virginia City’s director?

I loved him; he was a great director and I got along with him fine. I remember he’d say [in Hungarian accent], “I got to vait for der ‘goobers.’ “ He wanted to match the scenes and have the clouds look the same. And sure enough, ten, 15 minutes later, he’d say, “Here comes der ‘goobers,’ ” and we’d say, OK, let’s go do it.

Labels:

Arizona,

Errol Flynn,

Film History,

Humphrey Bogart,

John Ford,

Michael Curtiz,

Our Gang,

Pinocchio,

Sedona,

The Outlaw,

Virginia City,

Walt Disney,

Warner Bros.,

Westerns

Saturday, May 22, 2010

The Kid Stays in the Picture

Billy The Kid was a wanted man in 1930s-’40s Hollywood. After the release of MGM’s big budget Billy the Kid in 1930 (directed by King Vidor and starring Johnny Mack Brown), the character made a brief reappearance (played by uncredited Lynton Brent) in Tom Mix’s The Texas Bad Man, released by Universal Pictures in 1932. The desperado laid low before resurfacing in Republic’s Billy the Kid Returns (1938), this time as half of a dual role played by “king of the cowboys” Roy Rogers in his second starring film.

Two years later, ultralow-budget Producers Releasing Corp. (PRC) initiated a Saturday matinee series with Billy the Kid Outlawed (1940), which rewrote history by changing The Kid from horse-thieving gunman to benevolent Stetsoned Robin Hood. “B’’-movie cowboy Bob Steele played him in the first six films, released during the 1940-’41 season. Steele was replaced by former Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers/Tarzan star Buster Crabbe, who headlined thirteen more PRC Billy the Kid cheapies between 1941 and 1943. In these, the real-life character’s name (or alias) Billy Bonney was changed to Billy Carson, reportedly because of complaints that the films glorified a notorious criminal. Crabbe continued with the series for twenty-three more films into 1946.

Two years later, ultralow-budget Producers Releasing Corp. (PRC) initiated a Saturday matinee series with Billy the Kid Outlawed (1940), which rewrote history by changing The Kid from horse-thieving gunman to benevolent Stetsoned Robin Hood. “B’’-movie cowboy Bob Steele played him in the first six films, released during the 1940-’41 season. Steele was replaced by former Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers/Tarzan star Buster Crabbe, who headlined thirteen more PRC Billy the Kid cheapies between 1941 and 1943. In these, the real-life character’s name (or alias) Billy Bonney was changed to Billy Carson, reportedly because of complaints that the films glorified a notorious criminal. Crabbe continued with the series for twenty-three more films into 1946. MGM’s 1941 Billy the Kid remake with Robert Taylor was the first Technicolor movie shot in Sedona, but the studio with “more stars than there are in heaven” fretted over competition with millionaire Howard Hughes’ The Outlaw, finished early that same year, but not released for another 18 months, largely over censors’ objections to perceived erotic content and the camera’s leering fixation on Jane Russell’s breasts. Arizona location filming began in Tuba City, with additional photography slated for Sedona, but after two weeks Hughes abruptly ordered the production back to Hollywood without explanation. The Outlaw finally opened in San Francisco on February 5, 1943, but seven weeks later, after having grossed the then-tidy sum of $158,000, the eccentric Hughes, for reasons he never explained, pulled the picture out of circulation.

MGM’s 1941 Billy the Kid remake with Robert Taylor was the first Technicolor movie shot in Sedona, but the studio with “more stars than there are in heaven” fretted over competition with millionaire Howard Hughes’ The Outlaw, finished early that same year, but not released for another 18 months, largely over censors’ objections to perceived erotic content and the camera’s leering fixation on Jane Russell’s breasts. Arizona location filming began in Tuba City, with additional photography slated for Sedona, but after two weeks Hughes abruptly ordered the production back to Hollywood without explanation. The Outlaw finally opened in San Francisco on February 5, 1943, but seven weeks later, after having grossed the then-tidy sum of $158,000, the eccentric Hughes, for reasons he never explained, pulled the picture out of circulation.When Hughes decided to reissue The Outlaw in 1946, Hollywood’s self-censoring Breen office saw red over its naughty publicity campaign (“What are the two great reasons for Jane Russell’s rise to stardom?” and “How would you like to tussle with Russell?”), which led it to withdraw its seal of approval. Crazy-like-a-fox Hughes went ahead and re-released the picture anyway, to widespread local bans and canceled theater bookings. But proving there’s no such thing as bad publicity (especially when the buzz concerns sex), The Outlaw became a sensation despite widespread bad reviews, and eventually took in more than $3 million in the United States alone.––Joe McNeill

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)